We’re living in a world where concepts like RAG, fine-tuning, and LlamaIndex have become part of everyday conversation. But have you noticed? Everyone uses these as general knowledge terms. We know what they are on the surface. But we’ve never actually implemented them. Isn’t that a bit strange? We’ve never hands-on worked with these concepts. Let’s break this spell and dive into the details.

What Is RAG, Really?

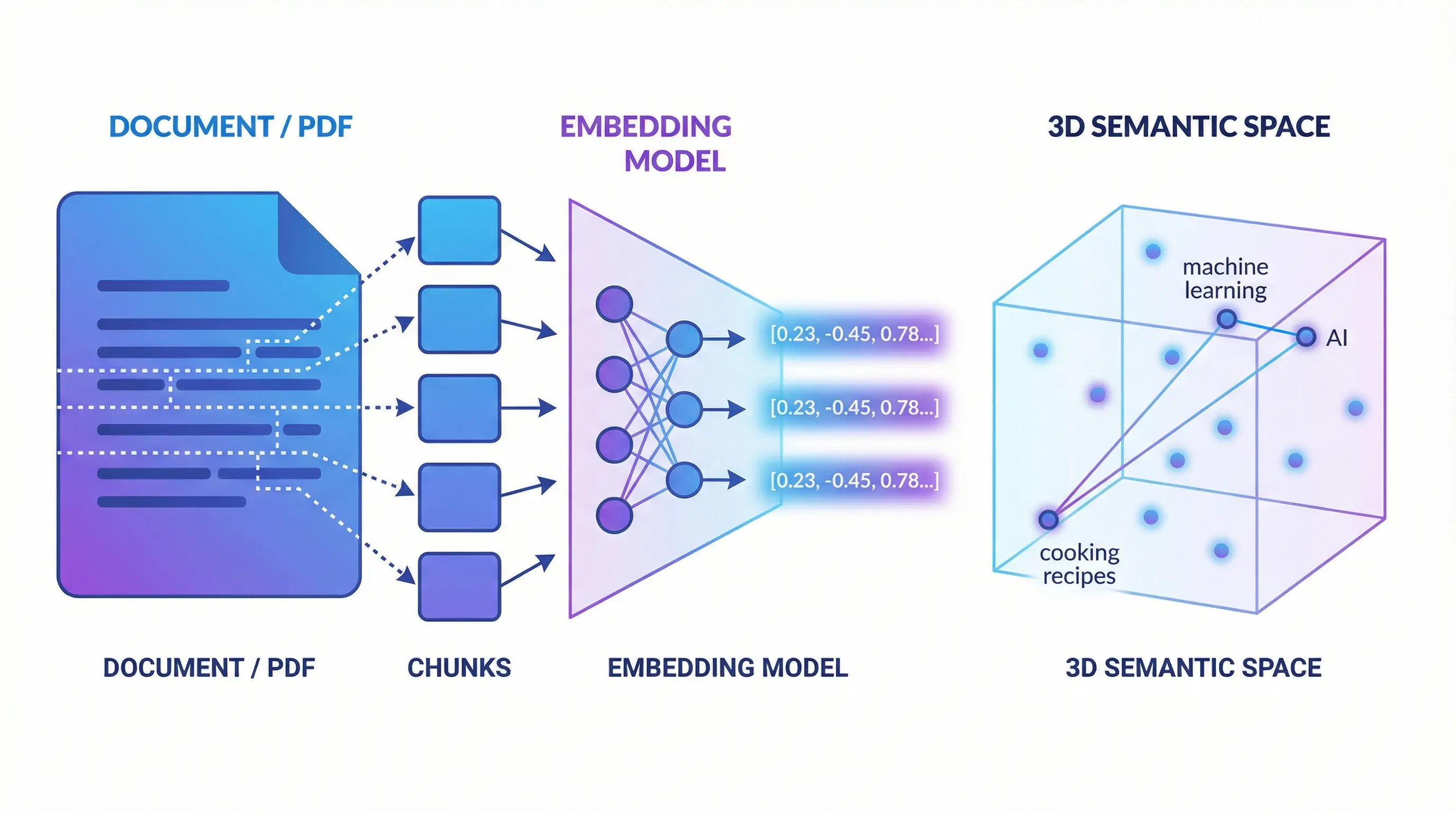

RAG is about splitting our data into the smallest meaningful pieces, converting them into semantic vectors (I really love this term because “embedding model” isn’t very descriptive), and storing them. When a query comes in, we convert it into a nice vector, search in the vector database, and voilà—the closest result is semantically the most relevant thing to us. Sounds confusing when explained like this, right? Let’s go step by step then.

Breaking Down to the Smallest Meaningful Pieces

We have a document. Let’s break it down to the smallest meaningful pieces. Why? Can’t we just keep it as is? No, we can’t. Because we’re going to semantically encode these meaningful pieces using an AI model and store them.

What does semantic encoding mean? It means encoding based on meaning. We need to convert the content into a meaningful vector using concepts like synonyms of words and semantic space. If this vector becomes a meaningful small piece, our search will be that much more successful.

Why Does Chunk Size Matter?

When choosing chunk size, we need to strike a balance: chunks that are too small lead to context loss (a single sentence might be meaningless on its own), while chunks that are too large add noise and reduce search quality. Generally, 256-512 tokens is a good starting point.

Also, using overlap between chunks is important. For example, having a 50-100 token overlap between 512-token chunks prevents sentences from being cut in the middle and helps preserve context.

def chunk_document(self, doc_data: Dict[str, Any]) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

try:

# Get the DoclingDocument object

document = doc_data.get("document")

if not document:

logger.warning("No document object found for chunking")

return []

# Create chunks using the DoclingDocument object

chunks = []

chunk_iter = self.chunker.chunk(document)

for idx, chunk in enumerate(chunk_iter):

chunk_data = {

"text": chunk.text,

"metadata": {

"chunk_index": idx,

"source": doc_data.get("source"),

**(doc_data.get("metadata", {}))

}

}

chunks.append(chunk_data)

logger.info(f"Created {len(chunks)} chunks")

return chunks

except Exception as e:

logger.error(f"Error chunking document: {e}")

return []

The code you see here converts a document coming from docling into n-items. It does this not by using length or whitespace characters, but with a smarter segmentation mechanism. Now we have a chunk list of a document broken into n-items.

What Do We Do with These Meaningful Pieces Now?

Now we’re going to “encode” these meaningful pieces using an LLM model. Encoding means converting our data into a platform’s language. That’s exactly what this encoding process is. We specifically call this vectorization. Because what comes out are vectors that the LLM can easily understand.

So how do we do this vectorization? Like this:

def embed_chunks(self, chunks: List[Dict[str, Any]]) -> List[Dict[str, Any]]:

try:

if not chunks:

return []

# Extract texts

texts = [chunk["text"] for chunk in chunks]

# Generate embeddings in batch

embeddings = self.embedding_model.encode(

texts,

batch_size=32,

show_progress_bar=False,

convert_to_numpy=True

)

# Add embeddings to chunks

for chunk, embedding in zip(chunks, embeddings):

chunk["embedding"] = embedding.tolist()

logger.info(f"Generated embeddings for {len(chunks)} chunks")

return chunks

except Exception as e:

logger.error(f"Error generating embeddings: {e}")

return []

Now we’ve embedded each item in our chunk list and converted it to a vector, saving it within the chunk. Our chunk list now contains this embedded and vectorized data. You can save this data to a vector database like Qdrant. Actually, you could also use OpenSearch, ChromaDB, or the pgvector extension in PostgreSQL. We used Qdrant as our example here.

We Saved It, But How Do We Search?

We say that our searches will be based on calculating vector distances and sorting the nearest vectors. That’s the theory. Earlier, we split our documents into small pieces (chunking), converted them to vectors, and saved them to a vector database.

But our search query is just text. How do we bring it into the vector space? The same way! Just like we converted those small pieces into vectors using embedding, we’ll convert our search queries into vectors the same way. Then we’ll search based on the vectors closest to this query vector.

# Generate query embedding

query_embedding = docling_service.embed_query(request.query)

if not query_embedding:

raise HTTPException(

status_code=500,

detail="Failed to generate query embedding"

)

# Search in Qdrant

results = qdrant_service.search(

query_vector=query_embedding,

limit=request.limit,

score_threshold=request.score_threshold,

filters=request.filters

)

# Format response

search_results = [

SearchResult(

text=result["text"],

source=result["source"],

score=result["score"],

metadata=result["metadata"]

)

for result in results

]

Here we embed the query value from the incoming request, convert it to a vector, and perform a vector space search. We’re essentially scoring based on the nearest vector distances within a certain limit.

Qdrant uses cosine similarity here. Normally, the closest distance would be 0 and far would be some number n, but Qdrant does the opposite with a score value: the most irrelevant results approach 0, while the most relevant results approach 1.

Conclusion

We’ve now designed a search system that works with English and can find semantically closest results—much smarter than traditional keyword-based searches.

In this example, we used the sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model. This model currently only supports English. If you’re working with content in other languages, you can use multilingual models like paraphrase-multilingual-MiniLM-L12-v2 or sentence-transformers/LaBSE.

In the next post, we’ll explore topics like hybrid search (BM25 + semantic), reranking, or different chunking strategies.

Source: github.com/turkersenturk/qsearch